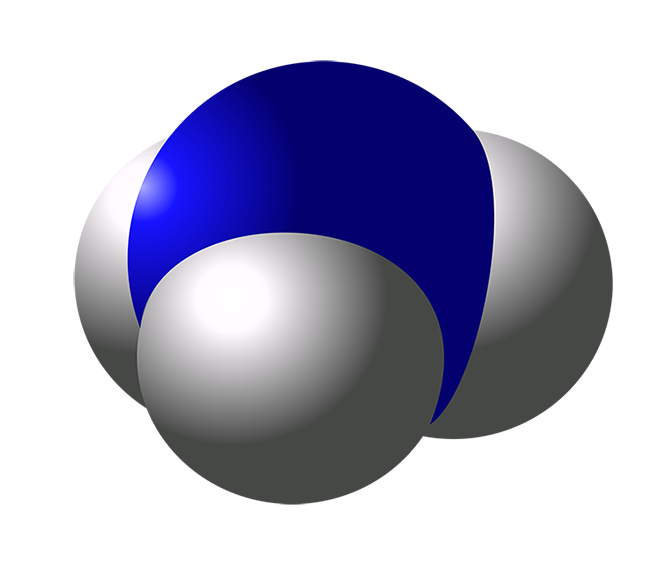

Already vital for food security, ammonia is emerging as an important source of low-carbon energy.

Ammonia, traditionally associated with fertilizers, is now drawing billions of dollars in investment from the U.S. government, Big Oil, and climate investors, who see its potential in decarbonizing industry and powering the shipping industry.

Recent developments, such as government support for a low-carbon ammonia production facility in Indiana and a private firm’s success in ship-to-ship ransfer of ammonia for fuel, indicate ammonia’s potential to provide a low carbon solution for both food and fuel.

Cleaner fertilizer

Historically, ammonia has been produced primarily for nitrogen fertilizer, through a process that uses fossil fuels and contributes substantial carbon emissions. However, recent initiatives focus on low-carbon ammonia, produced through processes that capture and sequester CO2.

The U.S. government in September announced a $1.56 billion loan to Wabash Valley Resources, a company that uses byproducts of oil refining to produce ammonia for fertilizer.

The Wabash Valley facility is intended to produce 500,000 metric tons of low-carbon ammonia annually and is strategically located near corn farms, which means lower transportation costs and greater security for the fertilizer supply chain.

The U.S. climate law of 2022 provided billions in tax credits for carbon capture, helping projects like Wabash Valley and others overcome the high costs of equipment and development. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, previously seen as unreliable, are gaining momentum due to these financial incentives and technological advancements. Companies such as CF Industries and Exxon are also pursuing carbon management projects in states like Mississippi and Louisiana, further expanding ammonia’s low-carbon footprint.

A fuel for shipping

Ammonia is also gaining traction as a low-carbon fuel. The Gulf Coast has seen major investments from Exxon Mobil and Abu Dhabi’s national oil company to develop low-emission ammonia projects. These projects aim to meet the rising demand for cleaner energy sources, particularly in the wake of supply chain disruptions caused by geopolitical tensions, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Shipping, which accounts for about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to UNCTAD, is a critical sector for decarbonization and ammonia is seen as a solution. A recent milestone was the world’s first ship-to-ship ammonia transfer, conducted in Port Dampier, Western Australia. This trial, a collaborative effort between Yara Clean Ammonia and the Pilbara Ports Authority, transferred approximately 2,700 tons of ammonia between two vessels.

The trial’s success paves the way for large-scale ammonia bunkering operations, positioning ammonia as a viable alternative to conventional marine fuels. The collaboration demonstrates that ammonia can be safely transferred and stored, marking a critical step in decarbonizing the shipping industry.

Yara Clean Ammonia says its global ammonia distribution network, with 15 ships and access to 18 ammonia terminals worldwide, uniquely positions the firm to scale ammonia’s role in decarbonization. It also suggests the possibility of ammonia as a fuel for other applications, the company says.

This development aligns with the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) new interim guidelines for using ammonia as a maritime fuel, expected to come into force by 2025.

Safety concerns

The IMO guidelines focus on the safe storage, detection, and handling of ammonia aboard ships, as ammonia is highly toxic and corrosive, making strict leak detection measures essential. For perspective, exposure to concentrations of 1,600 parts per million for 30 minutes can be fatal.

Another risk from ammonia for energy is the potential for incomplete ammonia combustion to release “nitrous oxide (N2O), a long-lived greenhouse gas around 300 times more potent than CO2 and a major contributor to the thinning of the stratospheric ozone layer,” according to Princeton University researchers.

The researchers report that proactive engineering practices can prevent these problems.

Solving such challenges can open the door to a new, low-carbon and widely available source of fuel.