As the global push for decarbonization increases the need for copper, experts say recycling must supplement traditional mining. In fact, some say, the solution to our growing copper demand may be close to home—inside our cupboards and drawers, where unused and obsolete electronics lie forgotten.

The backbone of all electrification, copper is essential to renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles, making it central to any sustainable energy transition.

A global copper shortage is on the horizon as demand, boosted by renewable energy projects and data centers, grows by 2.7-3% per year, according to Bloomberg. Bloomberg also predicts a supply-demand gap of 6.5 million tons by 2033. The UK will need nearly 350,000 tons of copper for wind turbines and solar panels alone by 2030, says the Royal Society of Chemistry.

The impending shortage is compounded by the fact that copper is becoming more difficult to mine, with most of the shallow, easily extractable deposits already depleted.

Mining for new copper carries severe environmental and social consequences. The industry is notorious for causing soil and water contamination, air pollution, and disruption of local biodiversity.

Industry experts suggest a simple yet powerful solution: urban mining. By recycling the copper already present in homes and businesses, we can significantly reduce reliance on raw copper, lessening both environmental impact and potential supply chain bottlenecks.

Discarded treasure in our homes

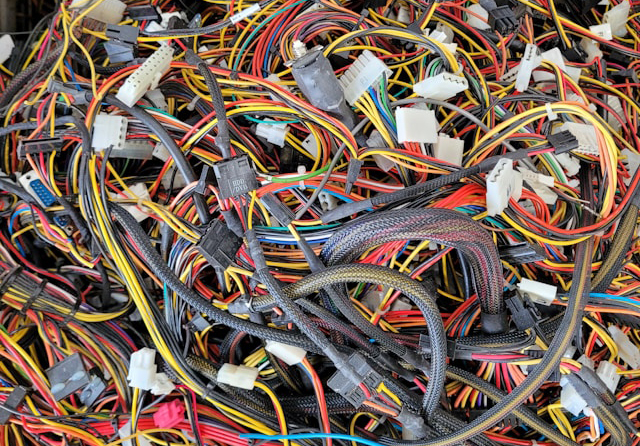

Recent research from Recycle Your Electricals reveals that the UK alone houses 823 million unused or discarded tech items, including 627 million cables. These seemingly insignificant items, hoarded in “drawers of doom” contain an estimated 38,449 tons of copper—enough to meet 30% of the UK’s copper demand for decarbonization projects like wind turbines by 2030, the research shows.

Cables and other discarded tech items are often overlooked in the discussion of waste management, but their contribution to e-waste is enormous.

Yet copper is 100% recyclable, and its reuse has a long tradition.

“It is estimated that two-thirds of the 690 million tonnes of copper produced in the last 100 years is still in productive use in applications such as computers, cars, cell phones, plumbing, motors or wires,” according to the International Copper Association.

Copper cable manufacturers like Nexans are stepping up their recycling efforts to meet the rising demand. The Nexans mill in Montreal, Canada, which has traditionally sourced all of its copper from ore, now produces copper rods from approximately 14% recycled metal, with plans to increase this proportion to 20%.

“We say to our customers: Your waste of today, your scrap of today is your energy of tomorrow, so bring back your scrap,” Nexans CEO Christopher Guérin tells the Associated Press.

Addressing the e-waste challenge

Despite a growing awareness of the environmental impacts of improper disposal, many people continue to throw away or hoard electronic items, unaware of the potential value within. A recent survey by Recycle Your Electricals finds 44% of respondents did not know that copper is the most commonly used metal in electrical cables.

To combat this lack of awareness, the organization has launched initiatives like “The Great Cable Challenge,” which aims to recycle one million cables across the UK. In conjunction with International E-Waste Day, the campaign has encouraged households, businesses, and local authorities to recycle anything with a plug, battery, or cable.

The benefits of this approach are twofold. First, it offers a practical solution to the growing copper crunch by reclaiming valuable materials already in circulation. Second, it helps address the broader environmental impacts of e-waste by reducing the need for raw material extraction while minimizing the amount of electrical waste sent to landfills.

It appears the solution to growing copper and other critical materials demand may not lie in deeper mining or larger mines, but rather in smarter recycling.